A Trafficked Child's Journey

London is considered as one of the greatest metropolitan cities in the world. People come from around the world to experience the rich heritage of the city, along with entertainment, theatre, and shopping.

London is considered as one of the greatest metropolitan cities in the world. People come from around the world to experience the rich heritage of the city, along with entertainment, theatre, and shopping.But London also has a dark side. Step up to any phone box and you will see cards plastered above the phones, inviting people into the sex trade. The telephone number is always a mobile number. And it’s most probable that the number you dial on Monday will be a different number on Tuesday.

No matter how fast British Telecom remove the cards, they’re back up, placed by a team adept at evading the police. ‘Young sex,’ New arrivals’ ‘Domination,’ – anything to lure the customer. And the consumer has a choice – hotel visits, or visit them ‘just a few steps away.’

Less than a five-minute walk from Piccadilly Circus you can find a single door, usually lodged between two street-shop businesses, where the person at the other end of the phone has directed you.

The girl who answers the door will speak little or no English. Her eyes will be imploring, but furtive. Any small talk you attempt to make will be limited because the girl has been shown recording devices in the room. She is strictly there for ‘business’ - up to twenty men a night.

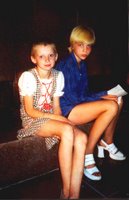

Meet Tereza. She is a sixteen-year-old prostitute. Tereza is from Moldova. In her broken English she tells you she’s Romanian, but to the familiar her accent gives her away. There is a bruise on the side of her neck. And she wears a long sleeved blouse, which barely covers the dark black bruises on both her wrists. She looks dreadful. Her eyes are recessed and dark, her hair is a mess, and she is trying to rapidly get down to business.

Tereza is a compilation of the hundreds, if not thousands, of girls from Moldova, Romania, Albania, and the Ukraine who are victims of child-sex traffickers. Virtually all of them have been enticed by either advertisements offering jobs for nannies, au pairs, hostesses, waitresses, and hotel staff. They’re promised accommodation, meals, and a basic salary. And they're encouraged to believe that they'll earn enough to send home to their families.

But the grim reality falls upon the girls very quickly and in most instances brutally.

For the Tereza’s the journey began when she answered a legitimate looking advertisement either in a local paper on the internet for workers to come to Amsterdam as an au pair. The woman she spoke with on the phone asked a number of leading questions, and invited her to come for an interview. At the interview, as a relationship was struck up, the woman interviewer gained valuable information about Tereza’s relatives. Where were her mother and father, did she have any brothers and sisters, how did she communicate with them. Most girls coming out of these villages are lucky to even have electricity; they certainly won’t have a telephone.

The interview may last for an hour or so and the interviewer will explain how difficult it is to get them into certain countries, and explain that they may have to first work in a restaurant in Italy while they are sorting the paperwork.

These innocent girls easily fall for the warm smiles and promises of these strangers. Sometimes they will show the applicants photos of Eastern European girls dressed in smart hotel uniforms, smiling and attentive, and obviously proud of their accomplishments.

And the phrases offered by the traffickers are always similar: ‘You’ll be so happy because you can finally rise above your current situation, you will be able to send money home to your family, as you work hard you will eventually be able to sponsor your family to come to England.’ All of these enticements are designed to lure the unsuspecting child into their hands.

And the journey begins. The girls return to their villages, tell their families (if they have any) how nice the lady was, how much it will help the family for them to leave and work, and what the photos of the accommodation looked like.

Trusting like lambs to slaughter, they leave. They naively hand all of their documents to their minders; passports..if they have one..state identification - anything that gives details about them. Usually at one point the girl will meet up with two other girls. And they will be introduced to their driver and a man who will ride in the front along with them. The woman who ‘hired’ them will not be travelling with the girls and usually promises that she will arrive in two days following.

This is their entrance into hell. They’ll bypass border guards, either through paying bribes, or by taking mountain paths. They’ll use boats to cross rivers. Usually there will be no threats or intimidation by the driver or his companion unless one of the girls become nervous and decide that they’ve ‘changed their mind.’ Usually their escorts do speak their language but pretend not to, therefore gaining further psychological advantage over the child.

Many of them will initially end up in Hungary, often Budapest. They will be taken to a nightclub that has several rooms above. Those rooms will contain 4 or 5 bunk beds where all the dancers stay, earlier victims of the enticement.

The girls are told they will dance. Should they object and say they were not hired for this – that they were to be au pairs and nannies, they’re told to shut their mouths. Some of them are badly beaten. And they’re told they have to dance in order to get to England.

There is no escape. The building is sealed. The only entrance or exit is constantly guarded. The girls are raped. Many of them are so young they have never even had a boyfriend. They are sold in the clubs to the highest bidders who queue up in response to calls from pimps that there is ‘fresh meat’ at the club.

The girls receive no money. They are immediately told they owe the traffickers for their transport and care and they must work it off. They live in fear, both physical and psychological. Often their captors play intricate psychological games with the girls. One man will take the role of the ‘nice person’ whilst the other man will be the violent torturer. These tactics are designed to pit the girls against one another, to ensure a continued flow of information about plans and resistance, and to increase the application of emotional torment against the girls.

Often, in the early hours of the morning, after being forced to dance and serve as prostitutes all night, the girls will be gathered into a lorry and driven north to Frankfurt, Amsterdam, or Brussels, where they become ‘fresh meat’ for the willing sex tourists. And now space has been made for the new arrivals in Budapest, who come across the borders almost daily. Some in up in other countries - sold as human organs. Their organs are harvested 'as required.'

The girls who are eventually smuggled into Britain come in the back of a lorry. Their enticement from the captors is that they have almost ‘worked off’ their debts and will be free in a few weeks’ time. The girls have become inured by their captures and seldom resist further. Always hanging over their heads is the fact that the captors know their families, where they live and some girls tell of stories where they have actually spoken to their younger sisters on a mobile phone, only to hear the child screaming moments later, as a man on the other end of the phone tortures the child. All of these tactics are designed to have maximum impact, and the events are assured to be shared by the enslaved girl with other girls around her.

I would love to say that these crimes are reducing. But sadly they’re actually increasing! Child-traffickers are becoming more and more adept at evading the police. The desperation of children and young people in Countries like Romania and Moldova are as bad today as it was sixteen years ago.

And should a girl be ‘rescued’ from their plight, often their treatment by police officials fails to recognise their basic human rights. In this regard there have been some positive changes taking place, but there is still a long way to go. Often the victims are too traumatised and frightened to give evidence and even if their captors are apprehended, the girl’s fear of retribution against their family and friends is such that they refuse to give evidence. There is also the social fear that they cannot return to their own village out of fear of being branded as a prostitute.

Many of the girls actively believe their original captors will be at an airport waiting for them to arrive and enslave them once again. The fear is palpable.

And their plight continues. Ostracised by their own country, treated as economic migrants by the countries they’ve ended in – these girls become new victims of a system that fails to have compassion for their needs. Unfamiliarity with the language, lack of money and proper documentation, mistrust of police or other authorities, lack of information, illegal immigration status, fear, shame, and isolation further reinforce the child’s dependence on the traffickers.

Each week, more and more experiences of families who knowingly sell their children into the child-sex trade continue. An entire family starving and freezing to death surrender all of their values in order to survive. They justify their actions by accepting and believing the lies they’re told, knowing full well that the ‘buyers’ are nothing more than pimps.

What is the solution?

It isn’t simple. And the problem is endemic. Villages need help in establishing trade skills for young people. They need the opportunity to develop job skills and growth opportunities. They also need education programmes to help today’s young identify the plight of young people who have gone before them. Education plays an important role.

Ultimately a small film that shows the journey of a child who has fallen afoul of traffickers, dubbed in local languages could help save hundreds of lives. It’s a challenging task, but the reward of saving so many lives must be worth the investment.

Can you help?

Labels: Child trafficking in Eastern Europe, Child trafficking into the UK, how to stop trafficking of children and women, Trafficking in Moldova and Romania, Trafficking routes in Eastern Europe